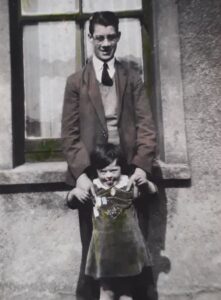

Meet Maura O’Mahony, my grandaunt. She’s here with her brother, my grandfather Michael, outside their house in Tonyville, Cork, just up the street from where their mother Minnie Verling lived at the time of her marriage.

Maura is about 4 or 5 here. My grandfather, who with the blazer, tie, and glasses looks well into his 20s, is actually about 17 or 18 we think. Maura was by all accounts his great favourite and he taught her to whistle, which she did all the time once she had mastered it.

Maura had Down syndrome. She was born in 1927 when her mother was 47 and her father 53, and she was probably the last of their seven children (I can’t find the birth date for one, Celia, which either means she was either born after 1921 – more recent birth records aren’t available on irishgenealogy.ie – or registered under a different name. I have found several of these incidents in my family tree).

Poor Maura died of scarlet fever in 1936 when she was just 9, in Cork Dental Hospital, at a time when scarlet fever, dyptheria, whooping cough and other illnesses were rampant. Because of the limit on what birth records are available I didn’t even know about her until my aunt referred to her while we were discussing other relatives. Even my father didn’t seem to know about her. Every now and then I like to make sure she isn’t forgotten.

She, alas, was not the only O’Mahoney (or Mahoney, or O’Mahony, the records alternate) from that family to die in childhood.

Her brother Daniel Joseph died in 1913 at the age of 3 of “hydrocephalus and exhaustion”. Heartbreakingly, the death record shows he died at home with his mother. He was their first child, and my relatives had not heard of him so I like to think I’ve contributed to research in that way. Hydrocephalus is a build-up of fluid in the brain and a child can be born with it – possibly because the mother was infected with mumps or measles while pregnant – or it can develop after birth. Either way it puts an enormous amount of pressure on the brain so I don’t like to think about what he went through. I do, though, like Maura, like to make sure he is not forgotten.

Daniel’s death, incidentally, is also the breaking of a chain. I can find Daniels in the family all the way back to the early 1800s, but after Daniel Joseph’s death I can find no more.

Child mortality also befell Minnie’s father’s children. I choose the words deliberately because Minnie (Mary) was born after an affair between her father Michael and a woman called Mary Madden. She was their only child, but Michael had had at least 11 with his wife, Martha Kenneally.

In many cases, I was unable to find a death registration, though I deduced that previously siblings had died because the names were reused. This seems grim, but it was a way of remembering the dead children. So Thomas William Verling, died 1868, is followed that same year by William James Verling. There are also a number of Marys in the family – Mary (Maria, 1863-67), Mary Kate (b. 1871), Mary Margaret (b.1873), and finally Mary (b.1875).

I did, and still do, think of them often. For if I don’t, who will?

When I did my initial detective work it seemed very much as if his entire line had died out (I could only find one child who lived to adulthood, Hannah, who dropped off the records after that) when his son Michael John died in 1882 in Cork Fever Hospital, now long gone. Until… an unexpected DNA match and message from Kansas City, where not one, not two, not three, but four of the missing Verling children (as they were to me at that time) had emigrated and built lives for themselves. They seem to have had in many ways a wild existence, which in itself befits the sort of wild reputation I can find for their father (a brute to Martha when drunk according to his daughter in the US, almost a saint according to his daughter Minnie). But more of that anon.

Pingback: Michael Verling – man overboard | DavidOMahony.ie