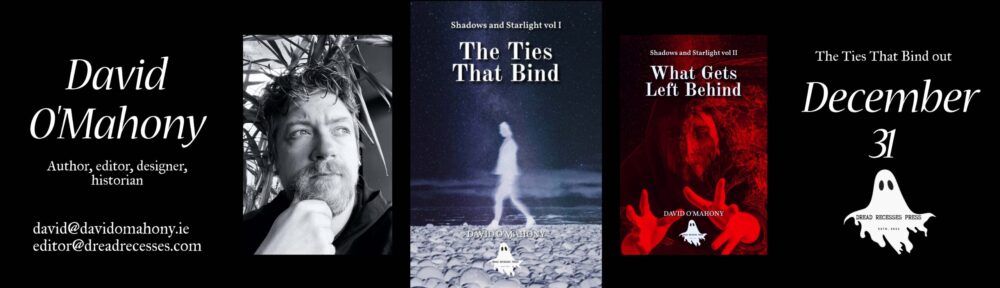

David O’Mahony is a horror and dark fantasy writer from Cork, Ireland. He specialises in ghost stories but can also be found writing contemporary fiction.

A prolific writer of short stories, he was a finalist in the 2024 Globe Soup primal fears competition and his first round entry to the 2024 NYC Midnight short story challenge was praised as a “creative, original take on the ghost story”. He has been published or is about to be published in Ireland, the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, India, and Thailand.

An award-winning newspaper designer, his non-fiction work tends to focus on history, in which he has a PhD, or on books and literary matters. Read his non-fiction for the Irish Examiner here.

When not writing he is assistant editor of the Irish Examiner, where he has picked up numerous awards for eye-catching front pages. One of his efforts, marking the publication of the mother and baby homes report and naming all the children who died at Bessborough mother and baby home, featured on Sky News, BBC, and CNN as well as being raised in parliament as an important historical document.

His front page on the murder of Lyra McKee was named front page of the year in 2019, and his team produced the front page of the year for 2020 as well as having an unprecedented double nomination. The Bessborough page won the award in 2021 and he won the 2023 award for Thank you, Vicky.

Story bylines:

Losing Your Grip, 2RulesofWriting.com, October 2023

Brotherly Love, davidomahony.ie, October 2023

Out of Time, Spillwords, December 2023

A Winter’s Wrath, Christmas of the Dead: Krampus Kountry, December 2023

Head Case, Flash of the Dead: Requiem, January 2024, and Exquisite Death, October 2024

Ghost of a Chance, Triumvirate volume 4, February 2024

Ties That Bind, 2RulesofWriting.com, February 2024, and Metastellar, July 2024

Atonement, Soulmate Syndrome: Certain Dark Things, March 2024

Blood Price, Masks of Sanity: Hidden In Plain Sight, April 2024

The Door, Spillwords, May 2024

Indistinct Background Character on a Field of Grey, 2RulesofWriting.com, May 2024

Sacrifices, Flash of the Undead, June 2024

Family Reunion, miniMAG, July 2024

Opportunity Knocks, Blood Moon Rising, July 2024

The Archaeological Findings of Ballybrassil, Cork: A Challenge to the Traditional Narrative, Perseid Prophecies, July 2024

Armageddon, AntiopdeanSF, August 2024

Holy Ground, Spillwords, September 2024

The Coachman, Children of the Dead: Shadow Playground, September 2024

Through the Gateway, Eldritch Encore: Stories Inspired by HP Lovecraft, September 2024

What Gets Left Behind, Stygian Lepus, September 2024

Family Tree, Mono No Aware, September 2024

Grave Tidings, Flash of the Dead: Halloween ’24, October 2024

Lantern Jack, Halloweenthology: Witches’ Brew, October 2024

Doorways, Exomoons–Natural, and Unnatural, Astronomical Bodies Orbiting Strange Planets – A Sci-Fi/Horror/Grimdark Anthology, December 2024

Whispers of the Wooded River, Perseid Prophecies, January 2025

Beneath the Skin, Infernal Delights, January 2025

Shadow of the Wyrm, Dragon Flight, January 2025

Onward, Petting Boo, January 2025 AND Frightening Friday (Twisted Dreams, 2025, forthcoming)

House of Sorrows (novelette, Graveside Press 2026, forthcoming)

Upon Reflection, The Gothic Gazette: Withered Love (Wicked Shadow Press, April 2025)

The Hungry Man, Parabnormal magazine (June 2025)

Sea Sacrifices, The Stranger At My Window (2025 forthcoming)

Grave Tidings, Readers’ Choice collection (Dark Holme Publishing, 2026)

Weighed Down, Channel the Dark vol 2, (Temple Dark Books, October 2025)

Seafoam, Lured into the Deep (Dragon Soul Press), May 2025

Amounting to Something, Sea of Monsters (Dragon Soul Press), June 2025

The Urge, Dark Descent: Whispers From Beyond (Dark Holme Press), March 2025

Moving On, Blood Moon Rising magazine, July 2025

Finding the Light, Spooky Sunday (Twisted Dreams Press, 2025, forthcoming)

Sic transit gloria mundi, Schlock! magazine (December 2025, forthcoming)