The humanities seem to always be under attack somewhere, whether through swingeing staff cutbacks in the UK or most emphatically now with Governor DeSantis’s “war on education” to enforce conformity of thinking across Florida universities that would actually reduce diversity and undermine academic freedoms.

It would be easy to simply state that both projects are driven by conservative authorities. It would be easy too to highlight that arts and humanities teach critical analytical and thinking skills that make for good dissidents, which historically, conservative authorities have not liked. So I won’t say that. I’ll say instead that the exposure to a wide range of philosophies (for want of a better word), critical approaches, and being trained in how to form arguments and spot bias are all huge and transferable assets that come with a humanities education.

Critical thinkers tend to suffer any time a government turns conservative and humanities subjects in universities take a hit if there’s a funding squeeze, as any academic working in a school of arts in this country can tell you from the last downturn.

I’m a historian, as well as a journalist and writer, and what’s happening in America alarms me greatly given how it is surely inevitable – particularly if DeSantis makes a serious run for the US presidency as anticipated – that a similar movement will bleed into Irish discourse, One would like to think that it wouldn’t, but those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, as George Santayana said, sometimes misquoted as by Churchill as “those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”.

History sometimes gets a bad rep as a subject that is difficult to study, full of dates and events. That’s an antiquated way of teaching and learning history. Dates are important, no doubt, but the emphasis long ago switched to how and why things happened more than simply when and who did them.

Some schools of thinking in history argue that the duty of a historian is to “tell it like it was”. EH Carr, back in the 1960s, argued that history (or history writing at least) was a sort of ongoing process between the events and the day of the historian. This is still an important point, because one’s understanding of and writing about the past can be shaped profoundly by one’s present, something which incidentally became a theme in my PhD. Other historians eschew that and focus on pure analysis. But there’s no point analysing something the reader (or listener) doesn’t know. Otherwise you’re just preaching to the converted and speaking into an echo chamber of perhaps a handful of people. Whatever the perspective, history is, rather than a dusty collection of ancient thoughts and events, a living, breathing thing that needs appreciation and even some nurturing.

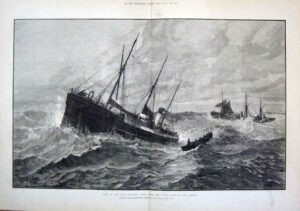

Take a walk around and you’ll walk through history. If I walk through Cork city centre, for instance, I can see the house my philandering great great grandfather Michael Verling lived in with his first family, the quays where he loaded and unloaded cargo, the customs office where my (not philandering) great great grandfather Daniel Mahoney worked following his naval career. I can visit churches where my ancestors were baptised. For years I walked past all these things not knowing they were part of my own history. I’ve spent the last number of years reclaiming it, if that makes sense.

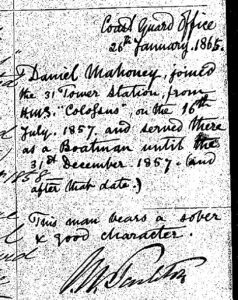

An extract from Daniel Mahoney’s naval record referring to his service in the coastguard from Hastings, England, after naval service in Crimea

They key point here is that, compared to four years ago, I actually know where my ancestors come from, and even that I have relatives hitherto unknown (and me to them) alive and well in Missouri. The analytical skills picked up from my training as a historian and journalist have helped me sift through the documentation. One might not immediately think of a genealogy project as history, but in this project alone I can show my family’s connection to the Crimean War, steam ferries up and down Cork Harbour, and the mining industry in Kansas and Missouri. These are parts of a wider story, a wider history, that of Ireland and its diaspora. Your family has its ties to history as well.

However, timelines and timespans can be lost on people (and to be fair it’s hard to visualise things). That said, a teacher of my acquaintance was recently tearing her hair out that so many of her students had no idea how long the human species had existed. The guesses ranged from 15,000 years to hundreds. Hundreds! It explains why my son, who is 9, asked me recently if we used horses to get around when I was a child. I’m not yet 40. I just feel old.

People don't have a strong intuitive sense of how much bigger 1 billion is than 1 million. 1 million seconds is about 11 days. 1 billion seconds is about 31.5 years.

— Paul Franz (@Paul_Franz) August 3, 2018

There isn’t a movement in history that hasn’t used, well, history to support itself one way or the other. There are sound reasons. Showing a tradition, for example. Drawing inspiration from the past is another. The problem is that a lack of historical literacy makes it difficult to understand when history is being co-opted for contemporary purposes – how some members of the current Sinn Féin lay claim to the anti-Treaty fighters who would not see them as successors? – and so don’t have the tools to challenge it. And it should be challenged as often as possible.