We have been telling stories about the things that terrify us since time immemorial.

We have done it in every medium ever invented, from oral campfire stories to religious illuminated manuscripts to wood etchings to cinema. There is no shortage of examples, and the beauty of horror (let’s just class it all as “horror fiction”) is that it is endlessly adaptable to the circumstances. Like science fiction, it’s a fantastic vehicle for social commentary, because you can make grotesque analogies with reality or real-life behaviours – Jordan Peele did this masterfully in Us and Get Out.

I can’t think of a single genre that’s been more influential on me than horror. It wasn’t just Stephen King, even though he was the first horror writer I was a fan of and for years he was the most numerous author in my own library (eventually match, then eclipsed by Terry Goodkind).

Although I’m also a big fan of science fiction, nothing can come close to horror for me really. The first book I can remember buying with my own money was a hardback Penguin Book of Horror Stories, now out of print, in a shop in Tralee, Co Kerry, which no longer exists (stop calling me old).

I go back to this maybe every 18 months or so. It holds such a prominent place in my formative years that I’m always convinced one of my favourite stories – about somebody who only discovers they’re living dead at the end when catching sight of themselves in a mirror – is in it, and yet it is not. I’ve never been able to trace the story, and as far as I know it was anonymous. My wife, incidentally, has suggested that it may have been a story I wanted to write but never did… so in all likelihood I will.

I had always aimed to be a fantasy fiction author. I fell head over heels for David and Leigh Eddings’ works while a teenager (the first one part of the Belgariad bought secondhand on a whim… I’ve only recently discovered the darkness in their past, see the comments). I loved, and still love, the world building aspects, the adventure, the ability to break rules with magic. And yet while I wrote the genesis of a couple of novels in my youth, they never completed themselves. I even did a whole preparatory study for a fantasy universe, a la the Eddings’ Rivan Codex, which was a bit of a goldmine in terms of trying to understand how to put something like that together.

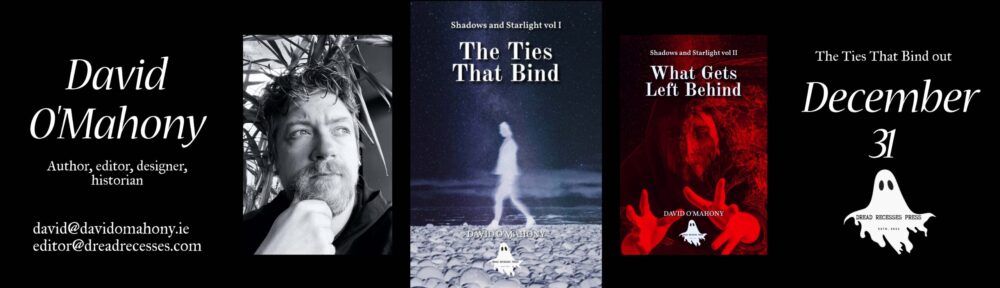

As I returned to writing recently, I worked out some fantasy-inspired stories, including one that’s paused in around the 17,000-word mark. But it turns out I have more of a flair for horror, and that I can use that genre to explore everything I have an interest in. A story of mine was recently published on 2RulesofWriting, and explores the idea of a ghost being haunted by himself. Other stories examine being trapped by pain of the past, while others dip back into the fantasy mythos.

The Guardian recently published a piece (and it’s really a rather interesting article) referring to the “horror fiction renaissance”, stating that horror “went away” in the 1990s to be replaced by other genres. Peele is quoted from a book on black horror that he views the genre “as catharsis through entertainment”.

This is actually not a new statement, though it captures the essence of it, and I remember it coming up as a theme in film studies while at university: The idea that a group can, communally, experience intense fear and emotions in a safe space (the cinema) with a defined end. A bit like a rollercoaster, which often is a good analogy for a horror film.

I’m not convinced by the article’s thesis that horror really went away. I’m not saying it’s entirely wrong, but rather that the genre has tended to just been reimagined. It blends easily with dystopian fiction (which itself goes back to Wollstonecraft Shelley’s The Last Man at least), science fiction, thrillers, pastoral scenes, whatever takes your fancy. Perhaps it is better to say that it became less visible, or less to the forefront culturally. Asian cinema has been producing horrors successfully, often remade for Western audiences (eg, Ring, The Grudge), and there is a superb range of anime horrors too.

Certainly, it is cyclical, like pretty much every other genre. Every now and again something comes out that breaks the conventions and establishes a new orthodoxy. Think the 1978 Halloween that more or less created the slasher genre. Think also of the Scream series, which resurrected the slasher genre but in a smart, self-referential sort of way. But while both of those series ended up prolific, they spawned innumerable imitators and the quality became diluted, as it typically does in every cultural mass movement.

The ability to self publish, and publish digitally first, has definitely allowed a flowering of newer subgenres in the last few years, and from a more diverse range of backgrounds, and there’s even a dedicated Irish publisher of science fiction and horror, Temple Dark Books. The vibrancy of #bookstagram and #booktok are also allowing new reads to get out in front of eyeballs faster than usual, even if it’s possible to drown in the sheer amount social media content (but it’s not just book-related). I follow a couple of horror-focused accounts on Instagram and I could easily (and gleefully) bankrupt myself buying up their recommendations.

Who knows what the future will hold? More cycles of innovation and stagnation, no doubt, but there will be constant innovation bubbling along in the background. I look forward to doing a better job of keeping in touch with it.

Happy Halloween!

I have read a good number of the books to my sons, and we have listened to them in audiobook as well. I read some of them as a child in the early 1990s (or thereabouts) and at this remove can’t recall word for word any of them, let alone say a particular phrase influenced my thinking. What I can certainly say though, and it was only apparent while reading Matilda to my son, that Matilda instilled in my a lifelong hatred of bullying (and fascism) and an appreciation for kindred spirit bookworms (as I was at Matilda’s age and well beyond), as well as a warm affinity for teachers.

I have read a good number of the books to my sons, and we have listened to them in audiobook as well. I read some of them as a child in the early 1990s (or thereabouts) and at this remove can’t recall word for word any of them, let alone say a particular phrase influenced my thinking. What I can certainly say though, and it was only apparent while reading Matilda to my son, that Matilda instilled in my a lifelong hatred of bullying (and fascism) and an appreciation for kindred spirit bookworms (as I was at Matilda’s age and well beyond), as well as a warm affinity for teachers.