As those who follow me on Twitter may know, for the past year or so I have set myself an annual reading challenge. This was originally an attempt to read 20 pages every day, but it sort of morphed into trying to read the equivalent of 20 pages a day over the course of a year, which works out at 7,300. Last year I managed to beat it, this year I’m slightly behind schedule. Such is life.

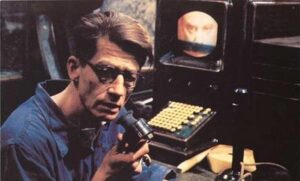

That preamble out of the way, I want to talk a bit about dystopias. Specifically Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, one of the greatest works of science fiction. It seems apt that a book about a society that burns books floated into my reading at a time when there is a serious threat to books in parts of America.

I have always loved dystopic fiction, perhaps ultimately because it forces us to confront wholescale world changes and how we cope with them. I like apocalyptic movies as well, so it’s clearly a genre I find appealing (I wrote about medieval ideas of the apocalypse too, but they’re quite different). This is a classic work, extremely short but essential reading.

In the book, a fireman (who burns books), Guy Montag, starts to come to the realisation that the extreme censorship and what he does for a living is wrong, and that there are other ways of living. Ultimately he decides to spend his days preserving books. That is a very simple summary of a book that has plenty of nuances, but it does the trick.

Ray Bradbury‘s style and the liveliness of the prose – and perhaps that much of the then fantastical technology such as immersive television experiences is not that far ahead of us now – make it easy to forget that the book was written in the early 1950s, when there were book burnings in America, and that one of his concerns is effectively the dumbing down of a population by the growth of television. But he wrote amid real fears about nuclear war – Hiroshima and Nagasaki being recent memories – anti-communist paranoia in America, and mass purges of intelligentsia and dissidents in Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Importantly, while it feels like a prophetic text, he himself would say it was about what might happen as opposed to what will happen. At its heart the book asks the question ‘what if people didn’t like books?’ and follows it through to its most extreme end to explore the sort of world that might result.

The most intriguing, and alarming, thing about Fahrenheit 451 is that the book-burning mandate didn’t come from the government or some autocracy. Rather, it grew organically because people felt they’d be better off. Montag is told, “Remember, the firemen are rarely necessary. The public itself stopped reading of its own accord.” That said, because this is relayed to the reader through dialogue it’s entirely possible that this is a story which was fed out as propaganda in favour of the changes, because it’s made obvious that the government is making what it deems best use of the situation.

News, for instance, is heavily sanitised at a time of nuclear war when bombers regularly fly over the homes of Montag and other characters. In fact the reader could ask if indeed cities across the United States (it’s only confirmed to by the US late on in the book) have been bombed already, given that it’s not clear if these are bombers returning from attacks or if they are attackers. Men are called up to the army, but none of their wives are particularly worried – they tell each other that it’s other women’s husbands who get killed.

Dissent exists, but it’s crushed. This dissent can be passive, such as through the mere existence of Montag’s neighbour Clarisse’s mere existence. She, free thinking and from a family that spends considerable time talking and interacting with one another as opposed to just existing, is in all her actions and force of personality the rank opposite of the sterile world that has been created, and while Montag is later told she was killed by a speeding car there is a strong inference that she was in fact killed by his captain. Thinking for oneself is a de facto crime.

The effects of not thinking for oneself are made clear by how Montag’s memory is in many cases weak: For instance, it is only toward the end of the novel that he can remember where he met his wife, and when he asks her this question earlier in the text she cannot remember either (though she places little importance on this).

Interestingly, there is the strong inference that people, at some level, realise that this is not how things need to be. Montag’s wife, who liberally takes sleeping pills, overdoses and he has to call medics to pump her stomach. The medics say they have multiple cases of this every night, suggesting that subconsciously even people who won’t question their reality openly are looking for an escape (a very final escape, but one all the same).

Sport, in this world, is the opiate of the masses (keep people occupied and makes them too tired to think really). But the key point about knowledge, and this is something I had in the back of my head when writing about the edits to Roald Dahl’s books (a decision now partially reversed), is that we need some sort of challenge if we are to evolve as individuals. As we are told in Fahrenheit 451: “We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while. How long is it since you were really bothered? About something important, about something real?”

This is not a new concept. In the sixth century, Gildas, who was a crusty old monk writing in post-Roman Britain, referred to how words, in his case vicious criticisms of power and hypocrisy, could be “darts” that lead to healing. He was writing about religious reform, but the point about using words to get under somebody’s skin (or simply into their heads) is the same.

It was, I’m sure, some subconscious filing quirk that had me put Fahrenheit 451 on top of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) on the shelves, given that my copies are not the same size (one of my usual filing systems). Both grim dystopias but in very different ways, with Orwell’s book putting more emphasis on the use of state surveillance and the abuse of overwhelming power, exemplified in particular by the re-editing of newspapers to match whatever current politics exists: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

I will explore dystopian fiction more in the coming weeks and months as I shake this website into shape.

I have read a good number of the books to my sons, and we have listened to them in audiobook as well. I read some of them as a child in the early 1990s (or thereabouts) and at this remove can’t recall word for word any of them, let alone say a particular phrase influenced my thinking. What I can certainly say though, and it was only apparent while reading Matilda to my son, that Matilda instilled in my a lifelong hatred of bullying (and fascism) and an appreciation for kindred spirit bookworms (as I was at Matilda’s age and well beyond), as well as a warm affinity for teachers.

I have read a good number of the books to my sons, and we have listened to them in audiobook as well. I read some of them as a child in the early 1990s (or thereabouts) and at this remove can’t recall word for word any of them, let alone say a particular phrase influenced my thinking. What I can certainly say though, and it was only apparent while reading Matilda to my son, that Matilda instilled in my a lifelong hatred of bullying (and fascism) and an appreciation for kindred spirit bookworms (as I was at Matilda’s age and well beyond), as well as a warm affinity for teachers.